Introduction

In part 1 of this series, I presented several of the approaches companies will use to address model-based systems engineering. All of those approaches in part 1 are doomed to be failures. Now let’s take a look at approaches that have been demonstrated to be successful. Part 2 addresses how to nurture an MBSE initiative.

Crawl-Walk-Run

Crawl Before Walking, Walk Before Running

One of the overarching principles I advocate for bringing MBSE to a company is the Crawl-Walk-Run approach. This was an overarching principle used at one company where our team successfully bootstrapped an MBSE process. It’s actually quite simple; learn to crawl before you try to walk, learn to walk before you try to run. Trying to go right from laying on your back to running a marathon is bound to end in tears, skinned knees and hands, and bruised egos. Going straight from non-standard functional block diagrams in Visio to SysML internal block diagrams in Cameo Architect will end pretty much the same way, plus cost a lot of money. Don’t make that mistake. Start with the basics, and build up from there. Crawl-Walk-Run applies to all the following sections.

Preferably Pick a Prepared Process

One of the earliest things a company must do as part of its MBSE initiative is to select an MBSE process to implement. I suggest selecting an established process, such as OOSEM from INCOSE, IBM’s Rational Harmony SE Process, IBM Rational Unified Process for Systems Engineering, Vitech Corporations’s STRATA process or one of several others. Why an established process? If your company is new to MBSE, it most likely doesn’t have the skills or expertise to develop a custom process. Start with something that already exists.

There are no hard and fast rules for selecting a process, as it depends on the needs of the company, its existing engineering knowledge base and the expectations of its customers. There are some heuristics you can use.

If object orientation is completely foreign to your technical staff, as well as your business development and project management staff, then selecting an object-oriented process is ill-advised. It’s easier to work with concepts your staff already understands, or that they can easily pick up on. You need to get the staff crawling before advancing to either walking or running.

If your typical customers prefer reports and drawings in a particularly format, then it’s best to select a process that supports these reports and formats. For example, if your primary customers and their products are very mode and state focused, your process should revolve around handling modes and states. These require a different approach and different process from products that are user-centric and are use case driven.

Customize the Complexity

Whatever prepared process you select, you will need to customize it to your own needs. Prepared processes are designed for any situation engineering can throw at them, and are generally complex. Most of your customization at this point will be subtracting unneeded complexity from the process. If the process has a series of steps that don’t apply to your company, pull them out of the pre-defined process as part of your customization. If your company is used to performing similar steps in a different order, feel free to change them up. Again, start crawling for your initial deployment before you try to walk.

With all this customization, you’re going to need to document your customized process. If it’s not written down, does it exist? If process documentation requires felling some trees in the forest and nobody reads the resulting paper, did it ever happen? Write your process down and formalize it. Be sure to apply your local configuration management processes for company processes, and make sure the process documents get distributed.

Merge the Maps

A pre-existing process will define the MBSE process using its own map of the process territory. You will need to create a cross-reference between the MBSE process and your standard engineering process. This is necessary for two reasons. First of all, you need to make sure your selected and customized MBSE process covers all significant aspects of your standard, non-MBSE process. For example, if your standard process requires functional decomposition, you should be able to describe how the MBSE process also covers the equivalent of functional decomposition, even though the details will be different. If you can’t make a cross reference between the two, you will need to understand and explain the exception.

Secondly, your engineers will need to grasp what they will be doing in an MBSE environment. Mapping an MBSE process against a non-MBSE process provides a necessary degree of familiarity for engineers. When they put the MBSE process into practice, they’ll be able to recognize that the new practice solves the same problems they were addressing with the old practice.

Without a “Rosetta Stone” for your process, your engineers simply won’t be able to translate it to something they understand. If they don’t understand the what and why of their tasks, they will put up resistance to your new process. Experience has shown that engineers can be stubborn that way.

Wield One Tool Well

Now that you’ve got a customized, MBSE process that suits your company needs, you’re going to have to put it

Only One Tool at a Time

into practice using an MBSE tool. Visio and Powerpoint are not going to make the cut for real MBSE, and using Excel databases to hold model entities actually somewhat scares me. (It should scare you too.) Pick a tool, but pick one. That’s right, you’re still at the crawling phase, and you want to have singular focus on a single MBSE tool. Find ones that support your process (you probably already know the tools) and make your best deal with the vendor. You’re going to need a lot of licenses and vendor support to make this work.

So far, you’ve got an MBSE process documented and you’ve got an MBSE tool. The next step is to translate your process into actual practice.

Pilot Projects Perfect Your Process for Practice

The next step in crawling from a set of MBSE process documentation to standing up a MBSE practice is to execute a pilot project using the new process. I recommend a simple project executed by the MBSE deployment team. The pilot should be common to your business and easy for the engineers to agree upon, once they see it. During this pilot, the deployment team learns to walk by executing their process. The team uses the defined methodology and selected tool, but perhaps more importantly, the team

documents every decision, menu selection and mouse click.

The methodology might very well start with a group sketching on white boards and making decisions in analysis. Document all the steps. For example, why is this a use case and some other alternative is not? Explain it. Why is an activity diagram using a fork here but a decision branch there? Explain it.

Next move the artifacts into the tool. How is a new project created? Show the menu selections and mouse clicks. How do you organize a standard project? Show how to create packages and folders, or your tool’s equivalent. How do I build a functional behavior diagram? Again, show all the steps in the tool.

Once you complete your pilot project, you’ll have a small team of experts stood up and ready to walk. Plus you’ll have all you need to create material for the next phase of nurturing.

Embrace Enthusiasm for Education and Training

As I wrote about before, you can’t just throw a process, or even a detailed practice, out into the engineering community and expect engineers to embrace it. Like an aged and experienced elephant, the engineering team will go where it wants and follow the familiar trails. Experience has shown that engineering teams can be stubborn that way as well. You can’t force a team, or an elephant.

But you can train it.

Effective Training is Essential

In fact, you need to make a commitment to training all of your system engineers in the MBSE process, and more importantly in the practice of it using the tool set. By “commitment,” I mean budget and time. If it’s important to the company, then the company will put money and time behind it. Money and time are the currencies of value in the language of corporations. A company that trains all its system engineers in MBSE clearly communicates the importance the company puts on the process, practice, and use of MBSE.

On the other hand, a company that expects engineers and instructors to participate in training during off days for free, or to take generic web-based training on their own time is communicating a very clear message: “MBSE training is not important. It’s value to the company, in our monetary language, is a big fat $0.00.”

Communicate the right message to nurture your MBSE initiative.

Call a Coach

Although your engineering teams will be well trained and ready to put the MBSE process and tools into practice, they are not really experts yet. They are walking and not yet running. They’re still developing paths through the MBSE jungle. You can make it easier for them by having a MBSE coaching team available for teams to call on demand. Instead of fumbling through an initial MBSE program startup, the engineering team can have a small team of experts available to help them, offer advice and make the program bootstrap go much faster.

Summary

The alliterative steps I’ve outlined here, from Picking a Prepared Process to Call a Coach, all support an MBSE initiative from crawling through walking. These aren’t all the good ideas for nurturing an MBSE initiative, but I consider them the main ones. If you have more ideas or additional experience, feel free to share in the comments.

The more effort you put into these nurturing efforts, the more likely you are to successfully stand up an MBSE process initiative and move it forward to the benefit of your company. Walking forward will take you far, but as your system engineering skills improve, you’ll want more options, more tools and higher quality outputs. You’ll probably want to add new MBSE tools and training beyond your initial selection so you can satisfy more customers. Or add new analytical techniques to your repertoire and train the team to use them in the tool. When you reach this stage you can truly say you’re up and running, and your MBSE initiative has reached it goals.

In the meantime, keep calm and MBSE on.

Over my decades of systems engineering, I’ve seen many variations of attempts to install modeling processes of some form or another into the system engineering process. I’ve learned to predict accurately whether a company will succeed or fail with their efforts, and I can predict it as early as the first 90 days of the start of an MBSE initiative.

Over my decades of systems engineering, I’ve seen many variations of attempts to install modeling processes of some form or another into the system engineering process. I’ve learned to predict accurately whether a company will succeed or fail with their efforts, and I can predict it as early as the first 90 days of the start of an MBSE initiative. If you are relying on grass-root efforts among the engineering staff to boot-strap your MBSE initiative, you’re dooming yourself to failure. Sure, the grass-roots, die-hard MBSE engineers are the ones who will jump aboard the MBSE band wagon when it shows up (if at all.) They even provide the fertilizer to help the seeds of MBSE to grow. On the other hand, they cannot direct other engineers to follow MBSE standards, nor direct change in programs or organizations.

If you are relying on grass-root efforts among the engineering staff to boot-strap your MBSE initiative, you’re dooming yourself to failure. Sure, the grass-roots, die-hard MBSE engineers are the ones who will jump aboard the MBSE band wagon when it shows up (if at all.) They even provide the fertilizer to help the seeds of MBSE to grow. On the other hand, they cannot direct other engineers to follow MBSE standards, nor direct change in programs or organizations. So maybe you’ve decided to fork over some of your budget and purchase a set of licenses for the latest and greatest MBSE tool. Then you push the tool to all your engineer’s computers and let them have at it. Nice thought, but ultimately a bad idea. The engineers probably don’t have the time or charge number to learn how to use the tool. If they do find time, each engineer will fumble around until they develop their own approach and methods. There is no ability to transfer tool skills between work groups or programs if everybody is engineering their models differently.

So maybe you’ve decided to fork over some of your budget and purchase a set of licenses for the latest and greatest MBSE tool. Then you push the tool to all your engineer’s computers and let them have at it. Nice thought, but ultimately a bad idea. The engineers probably don’t have the time or charge number to learn how to use the tool. If they do find time, each engineer will fumble around until they develop their own approach and methods. There is no ability to transfer tool skills between work groups or programs if everybody is engineering their models differently. On the other hand, down in the engineering management trenches, the staff knows there’s a much more important mandate: get the job done on schedule and make a profit. As a result, the MBSE implementation will be absolutely minimal, that is, just enough to check the box that the MBSE mandate was followed. MBSE will ultimately have little or no impact on the program.

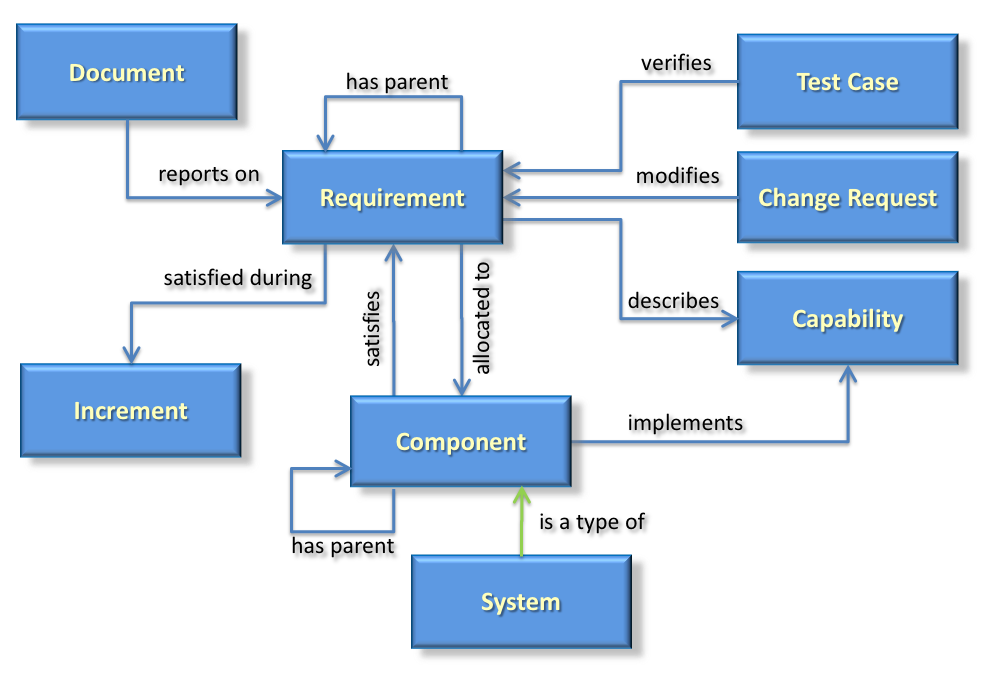

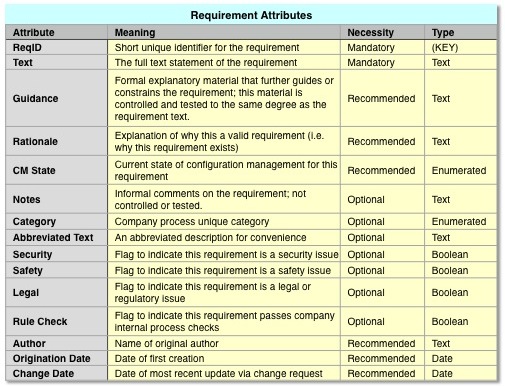

On the other hand, down in the engineering management trenches, the staff knows there’s a much more important mandate: get the job done on schedule and make a profit. As a result, the MBSE implementation will be absolutely minimal, that is, just enough to check the box that the MBSE mandate was followed. MBSE will ultimately have little or no impact on the program. Sure, Visio drawings might look better, but you can’t accurately engineer a solution using non-standard artist’s renditions of the proposed solution. You need the engineering drawings, and those come out of your MBSE process and tool using standard notation. You need ALL the engineering artifacts in your process to be in your MBSE tool’s database in order maintain correct and useful relationships from top to bottom.

Sure, Visio drawings might look better, but you can’t accurately engineer a solution using non-standard artist’s renditions of the proposed solution. You need the engineering drawings, and those come out of your MBSE process and tool using standard notation. You need ALL the engineering artifacts in your process to be in your MBSE tool’s database in order maintain correct and useful relationships from top to bottom.